The Battle of Palashi (also known as Plassey) was a historic battle that was fought between the British East India Company and the Nawab of Bengal Siraj Ud Daulah.

Though Nawab’s army was much larger (50,000 men), yet it was completely routed by a much smaller British Army composed of British Crown soldiers, European soldiers of the East India Company, and company soldiers from India. The company army won because of superior arms, use of treachery, timely tactics to save gunpowder, and better usage of the terrain.

As a result, the British were able to gain a foothold in the eastern part of India after their success in the peninsular part of the country, which ultimately led to their capture of North India in the upcoming century.

The Prelude to the Battle of Plassey

In the mid-18th century, the political landscape of Bengal was a complex weave of declining Mughal authority, regional power struggles, and the burgeoning influence of European trading companies.

The backdrop to this was the Carnatic Wars, a series of conflicts between the French and British East India Companies in South India from 1746 to 1763.

Clive emerged as a key company official with his success in the Battle of Arcot, where he held the Arcot fortress despite being outnumbered.

Alivardi Khan’s Ascension and Rule

In 1740, Alivardi Khan, a military commander under the Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah, rose to power in Bengal through a coup. He defeated his nephew and the then Nawab, Sarfaraz Khan, in the Battle of Giria, which was precipitated by a combination of strategic marriages, political maneuvering, and military prowess.

Alivardi Khan established himself as the new Nawab of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, marking the beginning of his dynasty. His reign was characterized by a delicate balance of resisting Maratha invasions while navigating the growing European presence. Alivardi Khan fortified his defenses, especially after the Marathas, under Raghuji Bhonsle, repeatedly raided Bengal. To counter these threats, he not only built up his military but also made strategic concessions to the British and French for their support against external threats.

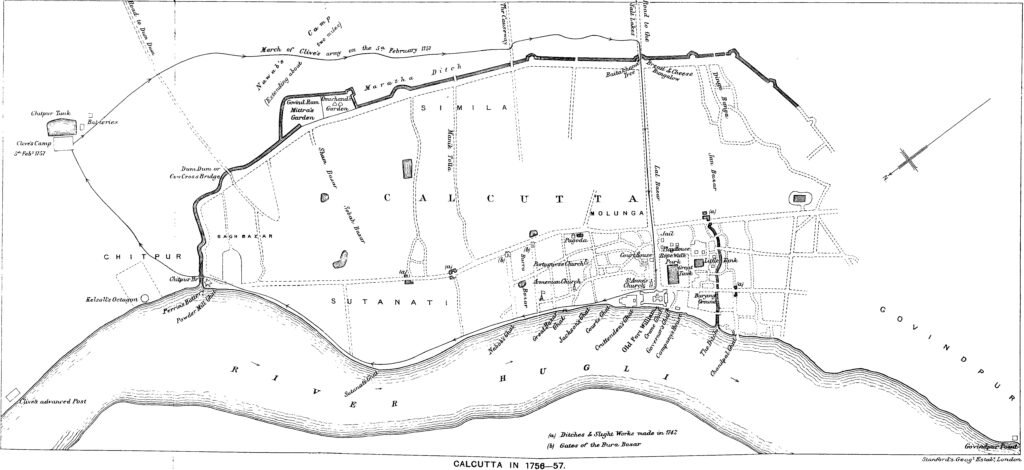

The Fortification of Calcutta and the Maratha Ditch

The British, under the East India Company, had fortified their settlement in Calcutta, which was initially established in 1690. As part of their defensive strategy, they constructed the “Maratha Ditch,” a moat that surrounded the city, named so because it was initially dug to fend off Maratha raids during Alivardi Khan’s time. This ditch was enhanced with ramparts and palisades, turning Calcutta into a formidable fortification by the mid-18th century. The fortification included Fort William, which was a military stronghold and also the symbol of British commercial and political aspirations in India.

Siraj Ud-Daulah’s Succession

Upon Alivardi Khan’s death on April 9, 1756, the succession was not straightforward. Alivardi Khan’s choice of successor was his grandson, Siraj ud-Daulah, over his half-sisters’ children, primarily because Siraj was the only male direct descendant.

Siraj’s claim was contested by rivals, including Mir Jafar, a seasoned military commander who harbored his own ambitions for the throne.

Siraj ud-Daulah’s early reign was marked by his determination to assert control over Bengal, especially against what he saw as overreaching European influence. His first significant act was against the British fortifications in Calcutta, which he viewed as an infringement on his sovereignty.

The Capture of Calcutta and the Black Hole Incident

On June 20, 1756, Siraj ud-Daulah’s forces attacked Calcutta, capturing the city in what would be remembered as the “Black Hole of Calcutta” incident. Here, British prisoners were reportedly confined in a small dungeon, leading to numerous deaths from suffocation and heat, though the exact details and casualty numbers have been subjects of historical debate. This event not only highlighted Siraj’s aggressive stance against the British but also precipitated a strong counteraction.

The British Response and Robert Clive

The British response was swift and decisive. Robert Clive, who had risen through the ranks from a clerk to a military leader, was dispatched from Madras to reclaim Calcutta. His arrival in January 1757 marked a turning point. By January 2, 1757, Calcutta was back in British hands, but the peace was fragile. Clive, seeing an opportunity for greater control, began negotiating with dissenting elements within Siraj’s court, particularly Mir Jafar, who was promised the throne in exchange for betraying Siraj.

For Clive, not moving ahead meant ceding territory and influence to the French, as Siraj was reported to be in talks with the French, making it possible to establish a French military presence there.

The Conspiracy and Prelude to Battle

The conspiracy between Mir Jafar and the British was facilitated through intermediaries like Khwaja Wajid, an Armenian merchant with significant influence. This clandestine agreement was part of a broader European strategy where the British aimed to leverage internal dissent for political gain, a tactic learned from the Carnatic Wars. The French, although less directly involved in Bengal at this point, contributed to the tension by supporting other regional powers in India, keeping the British on their toes.

As summer approached, both sides prepared for conflict. The British had superior artillery, disciplined troops, and the advantage of knowing the internal politics of Siraj’s court. Siraj ud-Daulah, though with a larger army, was undermined by betrayal from within. The stage was set for what would happen on June 23, 1757, at Plassey, where the battle would not just be fought with cannons and swords but with the intricate art of political betrayal.

This narrative, detailed to the smallest points, encapsulates the multifaceted prelude to the Battle of Plassey, where each action, from the Carnatic Wars’ influence to the strategic fortification of Calcutta and from Alivardi Khan’s rise to Siraj ud-Daulah’s fall, played a part in shaping one of the pivotal events in Indian history.

The Battle of Palashi (Plassey)

Forces Involved

- British Forces:

- Command: Led by Robert Clive, with Major Kilpatrick as the artillery commander.

- Numbers: Approximately 3,000 men, including:

- 950 European soldiers (British and a few French deserters).

- 600 Soldiers from the 39th Regiment of the Crown Army.

- 300 Soldiers from the Company’s 1st Madras European Regiment

- 2,100 Indian sepoys (native Indian soldiers in the British service).

- Artillery: 10 six-pounder guns, two light howitzers, mortars, and 100 artillerymen.

- 950 European soldiers (British and a few French deserters).

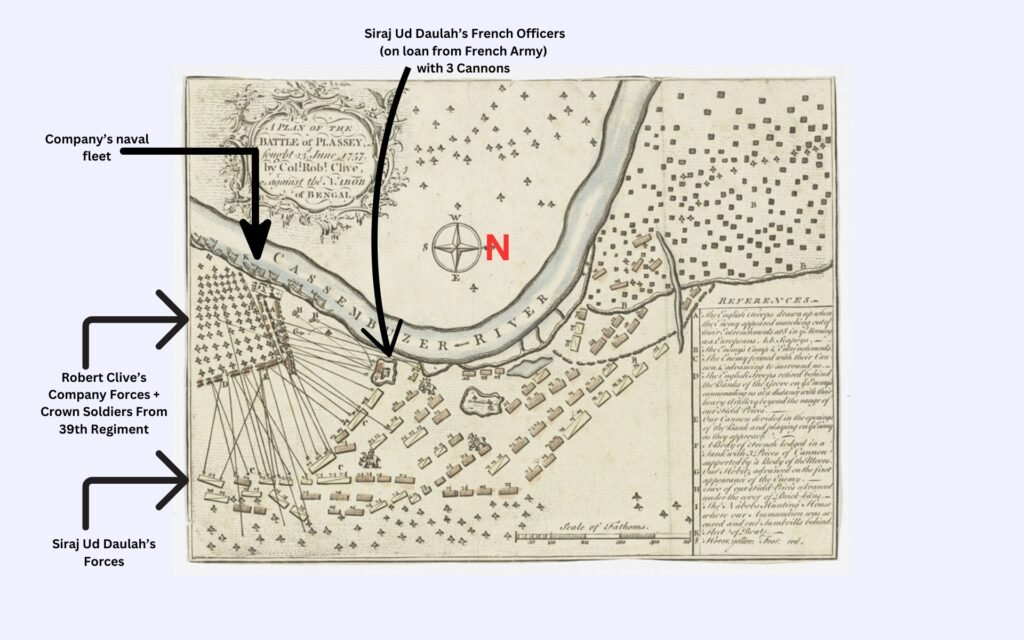

- Allies: Naval support from the Royal Navy’s ships in the Hooghly River with approx. 600 sailors, which provided both a morale boost and practical support like artillery fire.

- Forces of Siraj ud-Daulah:

- Command: Siraj ud-Daulah with several commanders, including Mir Jafar.

- Numbers: Variously estimated, but around 50,000 to 60,000 men, including:

- Cavalry: 15,000 to 20,000, a significant advantage in traditional Indian warfare.

- Infantry: 35,000 to 50,000, including both regular soldiers and irregulars.

- Artillery: Around 50 pieces, though less effective than the British due to poorer maintenance and training.

- Three artillery pieces and a few officers on loan from the French Army.

Equipment and Preparation

- British: Equipped with superior muskets, bayonets, and well-maintained artillery, their forces were disciplined and trained in European military tactics. The British also had better supply lines and logistics, ensuring their troops were well-fed and equipped.

- Bengal Forces: While they had more soldiers and cavalry, their equipment was less advanced. Many were armed with matchlock muskets, swords, and traditional Indian weapons like bows and arrows. The artillery was not as effectively deployed, partly due to the lack of coordination and the betrayal within the ranks.

Battle Events

June 23, 1757, Near the Village of Palashi (Plassey)

The village of Palashi was 160 km north of Calcutta (now Kolkata).

On a humid morning in Bengal, the river Bhagirathi (mentioned in the above map as the Cossimbazar River) flows quietly, unaware of the history about to unfold on its banks. Robert Clive, with his force, numbers about 3,000—950 Europeans, including some French deserters and 2,100 Indian sepoys. Their artillery, under Major Kilpatrick, includes eight six-pounder guns and other pieces strategically placed to leverage the terrain.

Now, facing them, Siraj ud-Daulah commands an army between 50,000 to 60,000 strong. His force includes a cavalry of 15,000 to 20,000, expected to sweep through the British lines, and an infantry of 35,000 to 50,000, with 50 artillery pieces at his disposal.

His command also has a small unit of 3 French Cannons and a few officers, taken on loan from the Imperial French Army.

However, Mir Jafar, one of his commanders, has already struck a deal with the British, promising inaction in exchange for the throne.

The Bengal Nawab’s army moved forward, thinking that the British ammunition might also have met the same fate as theirs and got fully drenched. However, the use of tarpaulins and the access to Nawab’s hunting quarters (beside the river and close to the British Camp) saved their powder charges.

Clive used the artillery to disrupt, demoralize, and decimate Siraj’s forces before they could fully engage. The cannon fire does its work, tearing through the advancing Bengal infantry and causing chaos. Siraj’s army withdrew in a hurry after the initial cannon charge dispersed them.

Mir Jafar’s forces (approx. 35,000 in numbers), supposed to be the right wing of Siraj’s army, do nothing. They stand by, as per their secret agreement with Clive, effectively neutralizing a significant portion of Siraj’s strength.

Other commanders, like Rai Durlabh and Jagat Seth, sensing the shift, either withdraw or defect. For Jagat Seth, there was also a risk of getting plundered by Siraj Ud Daulah. The latter was already low on funds and was at a revenue loss caused by the East India Company, which led to this war against the British.

By evening, the battle was over. The British have suffered minimal losses—23 dead and 50 wounded. Siraj ud-Daulah, realizing all was lost, fleed, but his escape was short-lived. He was later captured and executed.

Aftermath

Mir Jafar ascends the throne as the new Nawab, but under British influence, turning Bengal into a puppet state. This battle, class, wasn’t just about who had more soldiers or better guns; it was about the art of war meeting the dark alleyways of politics. Plassey was where the British learned they could expand their dominion not just by might but through cunning and betrayal.

Thus, Plassey stands as a lesson in history where the outcome of a battle was decided not only on the battlefield but in the shadows of power. This event marked the beginning of British ascendancy in India, setting the stage for further colonial expansion.